Not long ago, Salford was a vital part of the Manchester Coalfield, with a collection of coal pits including the Agecroft and Clifton Collieries.

The former closed fairly recently in 1991, and others within five miles of it have also closed within living memory.

Miners and their descendants take great pride in their work which contributed to and shaped the landscape of modern-day Britain.

Woody is back at Salford Civic Centre. Thanks to Powershift Blast Cleaning Ltd for cleaning, wood treatment & much needed minor repairs. Created by the Friends of Agecroft Colliery in 2016 he can carry on paying tribute to our brave Agecroft Colliery & Irwell Valley miners. pic.twitter.com/BPzuZJDP73

— Salford City Council (@SalfordCouncil) February 17, 2022

Salford’s coal mines produced coal for most of the city, and was transported to households and businesses down the Manchester, Bolton, and Bury Canal.

Some reading this may remember the tall shafts that once dominated the Salford skyline. Miners, supplies, equipment, and water would have once been transported down them to the ore.

Perfect – John Davies / Agecroft Colliery, Salford, 1983. pic.twitter.com/TmiMewXZ5C

— Andy Adams 📸 (@FlakPhoto) August 22, 2022

Andrew Knowles was the owner of Salford’s ‘premier pits’. Whilst his company’s output was initially for local use, Knowles expanded his production throughout the nineteenth century. He utilised the canal, as well as the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to transport the coal.

Andrew Knowles and his company are not remembered fondly by miners and their descendants.

The Miners’ Federation of Great Britain was established in 1888 to represent and coordinate the affairs of regional miners’ unions. Workers from Knowles’ pits who joined the federation were locked out and the company managed to defeat attempts to unionise the workforce.

Knowles’ legacy is an unpleasant one – he is remembered as a powerful man, with ‘the power of life and death’ in his hands. Yet, he nor his company showed any regard for the workforce beneath them.

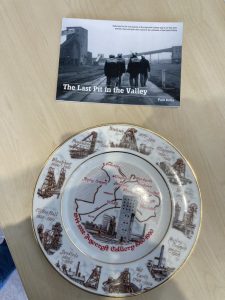

Paul Kelly, author of ‘The Last Pit in the Valley’, comes from a mining family and worked in Agecroft Colliery himself for twelve years.

As part of Community and Local History Month, he delivered a talk on Salford’s former collieries at Swinton Library on Tuesday 9th May.

Mr Kelly reminisced on the superstitions of miners, recalling how whistling was not allowed in the pit, and how forgetting something once you’d left for work meant going back and spending the rest of the day at home.

The former miner also recalled visits to the colliery from politicians, crewmate from the HMS Conqueror, nurses, schools, and an encounter with the chairman of the National Coal Board – Sir Ian MacGregor.

Mr Kelly believes we owe a lot to the children and families who were sent to the mines from a young age to work and provide coal for the community. Collieries were often family enterprises, with children from as young as the age of five being sent to the pits.

At the start of the Second World War, a young Eric Bartholomew (better known to many by his later stage name, Eric Morecambe) met a young Ernie Wise and the two men formed comedy double act Morecambe and Wise.

However, due to the two young men coming of age for their War Service, Mr Bartholomew was conscripted to become a Bevin Boy and was sent to work as a coal miner.

The Bevin Boys were conscripted to increase the rate of coal production which had declined through the early years of the Second World War. Bartholomew was sent to work in Accrington from May 1944 onwards, but Mr Kelly revealed that he also spent time working in Salford’s pits.

In fact, Irwell Valley Mining Project – a local group chaired by Mr Kelly – wish to commemorate his wartime efforts in Salford with a plaque.

The community group formed in 2012 to raise awareness of Salford’s coal mining past.

They work with schools, organisations, and members of the community to educate local people about Salford’s mining heritage by performing exhibitions, talks, and providing information packs.

In 2013, the group secured funding from the National Lottery to erect a monument at the former entrance to Agecroft Colliery. They now plan to erect a monument for each colliery in the Irwell Valley.

They have also prepared a second plaque. This will be unveiled soon at St Thomas’ Church in Pendleton to commemorate those who worked and died in the Pendleton Colliery which used to be on Whit Lane.

In fact, the first people to be buried at the church in 1829 were miners and their graves are still distinguishable to this day.

Mr Kelly emphasised the importance of this. Often, miners who were killed in an explosion were simply left in the ground to form a mass grave. He pondered whether an official grave and headstones had been arranged for these miners in an attempt to clear conscience.

Terraced houses that were built on Langley Road for workers and their families in the Pendleton Pit are still there today. However, much of Salford’s mining past has now been demolished, concreted over, and sadly forgotten by many.

This is why the work of Mr Kelly and the Irwell Valley Mining Project, and events such as Community and Local History Month are so important.

Miners risked their lives travelling down into the pits every day, where levels of methane where high and many died from explosions due to combustion.

This happened in 1885 in the Clifton Hall Colliery. A massive explosion occurred that shook the ground for half a mile around, killing 178 men and boys.

Clifton Hall Colliery by Henry Edward Tidmarsh (1854 -1939) pic.twitter.com/VUnq4EYyc8

— Grim Art (@GrimArtGroup) June 5, 2021

Salford’s colliery past now lies beneath tonnes of concrete – hidden below retail parks, supermarkets, and fast-food restaurants.

Yet the legacy of the miners still lives strongly today in their descendants.

In fact, when I attended Mr Kelly’s talk, I spoke to another attendee after the event. He revealed to me an old newspaper clipping he had been sent by a family member about a miner who had died in the Clifton Colliery in the early 1900s.

Frank Rothwell was a miner who died at the young age of 39 after being accidentally killed whilst down in the mines. The attendee revealed that Mr Rothwell was his grandfather.

The man had never known his grandfather, and his father was also no longer alive so he knew very little about his family’s mining heritage.

However, he was able to speak to Paul Kelly after his talk and find out where his grandfather would likely be buried – something his family had never known until that day.

And that’s why Community and Local History Month and the work of people such as Paul Kelly are so important. We often forget to ask the important questions about our family and local community history until it’s too late.

Through the workings of groups such as the Irwell Valley Mining Project, people are ensuring that the legacy of those who shaped our lives and society today are never forgotten.

Find out more about Irwell Valley Mining Project and Salford’s mining history here.

Recent Comments